a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

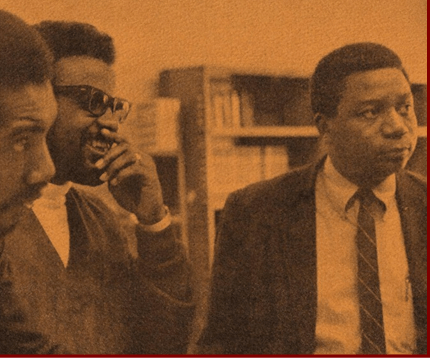

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

At least one major thing has changed since May 23, 1968, when a New York City Transit cop shot Dumas dead on the southbound platform of the 125th Street subway station on the Lexington Avenue line running under Harlem.

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

For the same reasons, the reader who confronts Dumas’ poetry in the reprinted edition of “Knees of a Natural Man” (forthcoming on October 30 from Flood Editions) will find a startlingly original contemporary. In these 165 poems, curated by East St. Louis’ own Eugene B. Redmond, we encounter the quintessential young, brilliantly burning Black man, enflamed by violence against his people and oppression, alert to the possibilities of Blackness reaching all the way back to before ancient Egypt.

At least one major thing has changed since May 23, 1968, when a New York City Transit cop shot Dumas dead on the southbound platform of the 125th Street subway station on the Lexington Avenue line running under Harlem.

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

For the same reasons, the reader who confronts Dumas’ poetry in the reprinted edition of “Knees of a Natural Man” (forthcoming on October 30 from Flood Editions) will find a startlingly original contemporary. In these 165 poems, curated by East St. Louis’ own Eugene B. Redmond, we encounter the quintessential young, brilliantly burning Black man, enflamed by violence against his people and oppression, alert to the possibilities of Blackness reaching all the way back to before ancient Egypt.

At least one major thing has changed since May 23, 1968, when a New York City Transit cop shot Dumas dead on the southbound platform of the 125th Street subway station on the Lexington Avenue line running under Harlem.

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

By Chris King of the St. Louis American Sep 5, 2020 Updated Sep 5, 2020

If Henry Dumas were still alive today, it’s possible that the world would be different because he would have transformed it in some way. If, however, he was to suddenly return to life today, in the way that long-out-of-print books can suddenly be reprinted, he would be amazed. He would be amazed to discover, 52 years after he was killed, that Black people like himself still confront the same problems and possibilities.

For the same reasons, the reader who confronts Dumas’ poetry in the reprinted edition of “Knees of a Natural Man” (forthcoming on October 30 from Flood Editions) will find a startlingly original contemporary. In these 165 poems, curated by East St. Louis’ own Eugene B. Redmond, we encounter the quintessential young, brilliantly burning Black man, enflamed by violence against his people and oppression, alert to the possibilities of Blackness reaching all the way back to before ancient Egypt.

At least one major thing has changed since May 23, 1968, when a New York City Transit cop shot Dumas dead on the southbound platform of the 125th Street subway station on the Lexington Avenue line running under Harlem.

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

By Chris King of the St. Louis American Sep 5, 2020 Updated Sep 5, 2020

If Henry Dumas were still alive today, it’s possible that the world would be different because he would have transformed it in some way. If, however, he was to suddenly return to life today, in the way that long-out-of-print books can suddenly be reprinted, he would be amazed. He would be amazed to discover, 52 years after he was killed, that Black people like himself still confront the same problems and possibilities.

For the same reasons, the reader who confronts Dumas’ poetry in the reprinted edition of “Knees of a Natural Man” (forthcoming on October 30 from Flood Editions) will find a startlingly original contemporary. In these 165 poems, curated by East St. Louis’ own Eugene B. Redmond, we encounter the quintessential young, brilliantly burning Black man, enflamed by violence against his people and oppression, alert to the possibilities of Blackness reaching all the way back to before ancient Egypt.

At least one major thing has changed since May 23, 1968, when a New York City Transit cop shot Dumas dead on the southbound platform of the 125th Street subway station on the Lexington Avenue line running under Harlem.

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.

By Chris King of the St. Louis American Sep 5, 2020 Updated Sep 5, 2020

If Henry Dumas were still alive today, it’s possible that the world would be different because he would have transformed it in some way. If, however, he was to suddenly return to life today, in the way that long-out-of-print books can suddenly be reprinted, he would be amazed. He would be amazed to discover, 52 years after he was killed, that Black people like himself still confront the same problems and possibilities.

For the same reasons, the reader who confronts Dumas’ poetry in the reprinted edition of “Knees of a Natural Man” (forthcoming on October 30 from Flood Editions) will find a startlingly original contemporary. In these 165 poems, curated by East St. Louis’ own Eugene B. Redmond, we encounter the quintessential young, brilliantly burning Black man, enflamed by violence against his people and oppression, alert to the possibilities of Blackness reaching all the way back to before ancient Egypt.

At least one major thing has changed since May 23, 1968, when a New York City Transit cop shot Dumas dead on the southbound platform of the 125th Street subway station on the Lexington Avenue line running under Harlem.

Henry Dumas (from left), William G. Davis and Eugene B. Redmond in 1967, during their tenure as teacher-counselors at the Experiment in Higher Education at Southern Illinois University – East St. Louis. Photo courtesy of Eugene B. Redmond

Today, a bystander video might go around the world and have people chanting “Henry Dumas” in the streets weeks before the police sheepishly released his killer’s name. In 1968, Du- mas was an unnamed “33-year-old man” (not even a “Black man,” certainly not a “natural man”) buried in a three-para- graph report in the middle of page 5 of the Herald Statesman (straight out of Yonkers). His killer, Peter Bienkowski, was named outright because he faced no threat of prosecution.

No witness ever testified to counter or complicate the police shooter’s narrative captured in the curt headline “Knife Brings Death Bullet.”

So, Dumas is an ancestor of today’s Black Lives Matter protest movement and its contemporary martyrs, but not only because a cop killed him. Many of today’s movement leaders have artistic vocations that they suspended to save lives or that they find ways to use in their activism. Today’s artivists will find Henry Dumas waking up in ways they are waking up, praising much of what they praise, summoning the strength to heal the pain that they are trying to heal. A natural man or woman needs his or her (or their) knees to kneel to pray. Today’s artivists will find Dumas praying their prayers before they were born.

Dumas came to East St. Louis in the summer of 1967 to teach with Katherine Dunham for the blink of an eye, and that is how he be- friended Redmond. Because Redmond has outlived his friend for more than 50 years it’s difficult to imagine him as the younger man, but Dumas was several years older than Redmond and (arguably) more evolved in his poetic practice during their all-too-brief time together. Dumas’ poetry (and fiction) survived largely because of Redmond, and in the survivor’s decades-long efforts to collect, cu- rate, edit, publish and now reprint Dumas’ work, we see a debt of gratitude that will never be fully paid.

I had been alive only half a year in 1967 when Dumas arrived in East St. Louis and assured the future survival of his poetry by meeting Redmond. I was a white boy seven miles (and several centuries of slavery) away in the Sundown Town of Granite City. But, in 1989, when Redmond first secured publication of “Knees of a Natural Man,” I was Redmond’s friend and understudy in the St. Louis perfor- mance poetry scene. Then, as now, Redmond never spoke for more than a minute without mentioning or quoting Henry Dumas.

There is no telling how many thousands of people have read Dumas because Redmond talked to them about Dumas assuming that they had read Dumas – or would, eventually, after hearing Dumas spill out of Redmond’s mouth. Redmond became even better friends with Toni Morrison (who is among the thousands of Redmond-spurred Dumas readers) and Maya Angelou. I can remember being a 23-year-old white guy running around with a 52-year-old Redmond, who was always saying, “Maya,” “Dumas,” “Morrison” – not to mention “Baraka,” “Miles,” “Bluiett,” “Mor Thiam” (the father of Akon), all his personal friends – and me thinking, “I’ve got to catch up, I’ve got to get to know this stuff, this stuff is important, this stuff is going to teach me how to write, this stuff is going to teach me how to live.”

this honey you gave me has turned to tears

Dumas wrote, and Redmond curated, dripping from your fingers

a lost sweetness

but you can get it back. When they kill a man, you can never bring him back, but when you publish a poet, even if the book goes out of print, you can bring it back into print. You can get it back. You can bring him back.