New research finds growing racial disparities in overdose mortality and a major shift in geographic trends of the opioids crisis

Between 2009 and 2019, overdose deaths in the United States involving opioids and stimulant drugs, such as cocaine and methamphetamine, surged compared to deaths from stimulants alone. Fatalities linked specifically to cocaine combined with opioids rose by nearly 450%, an alarming trend fueled by the growing contamination of non-opioid drugs by fentanyl, an extremely potent synthetic opioid. By 2019, more than three-quarters of deaths involving cocaine and half of those involving methamphetamine or other stimulants also involved opioids.

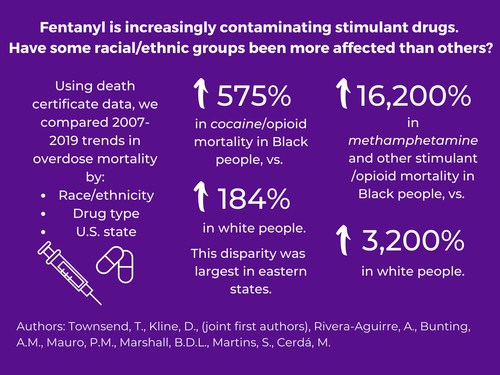

In the first study of its kind, researchers from NYU Grossman School of Medicine and Wake Forest University School of Medicine analyzed the trend of rising opioid/stimulant deaths by racial/ethnic groups and by state. The findings, publid online February 8, 2022 in the American Journal of Epidemiology, indicated that while overdose deaths from opioids and stimulants rose across all racial groups and across the country, opioid/stimulant deaths among Black Americans increased at more than three times the rate as non-Hispanic white people—particularly in eastern states. Analysis also found a significant increase in overdose opioid and stimulant deaths among Hispanic and Asian Americans.

The team of investigators found that between 2007 and 2019, the rate of Black Americans dying from opioids and cocaine climbed by 575 percent, compared to 184 percent among white people. While mortality from methamphetamine and other stimulants (MOS) remained at lower levels in 2019 than cocaine/opioid mortality, it has increased dramatically in recent years among Black Americans. MOS/opioid mortality rose 16,200 percent in Black people versus 3,200 percent in white people.

“While all racial and ethnic groups we examined are dying in greater numbers from opioids combined with stimulants, we are alarmed to see these trends worsening so much faster in marginalized communities that have historically been less affected by the current epidemic,” says Tarlise Townsend, PhD, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy in the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone, and lead author of the study. “We need to be targeting harm reduction and treatment strategies to those who are being hardest hit.”

How the Study was Conducted

To identify deaths caused by opioids in combination with stimulants, the team of investigators analyzed individual death certificate data for all deaths coded as overdose from the 2007-2019 National Center for Health Statistics. Deaths were grouped by race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic Asian American and Pacific Islander) as well as by state. The researchers analyzed deaths from opioids in combination with cocaine, as well as with methamphetamine and other stimulants (MOS). In order to disaggregate data by racial groups and states, the scientists used special statistical modeling to account for small sample sizes. The analysis found:

- From 2007 to 2019, Black Americans experienced sharper increases in both cocaine/opioid and MOS/opioid mortality compared to white Americans, particularly in eastern states.

- The largest Black/white disparity was in MOS/opioid mortality in the Midwest.

- By 2019, rates of cocaine/opioid mortality in Black Americans were considerably higher in 47 states than among white Americans.

- In the South, deaths from cocaine and opioids grew 26 percent per year in Black people, 27 percent per year in Hispanic people, and 12 percent per year in non-Hispanic white people

- MOS/opioid death rates among Black people increased 66% per year in the Northeast, 72 percent per year in the Midwest, and 57 percent in the South.

- MOS/opioid death rates among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders increased faster than in white people along the West and Northeast.

- Among Hispanic people, MOS/opioid death rates grew faster than among white people in the West, Northeast, and upper Midwest.

The study’s findings raise some important public health challenges, says Townsend. People who primarily use stimulants may not identify as people who use opioids, making them less likely to obtain opioid-related harm reduction services such as fentanyl test strips and take-home naloxone.

“Our findings bolster the argument that overdose prevention efforts should target not only people who use opioids, but also those who primarily use cocaine, methamphetamine, and other stimulants,” said Magdalena Cerdá, DrPH, professor and director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy in the Department of Population Health at NYU Langone Health, and the study’s senior author. “Because of structural and systemic racism, adequate access to harm reduction and evidence-based substance use disorder treatment services is lacking in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods. More state and federal funding for these programs are needed.”

“Our results showed that opioid/stimulant mortality varies considerably from state to state, even within a single region. This provides critical information to policymakers and others about the severity and evolution of the crisis in their state,” added David Kline, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Biostatistics and Data Science in the Division of Public Health Sciences at Wake Forest School of Medicine, and joint lead author of the study.

Future research is urgently needed to gain a better understanding of the causes of rising stimulant/opioid overdose mortality, says Cerdá, particularly in Black and Hispanic communities, and the types of solutions that will be most effective to address this emerging problem.

In addition to Townsend and Cerdá, study co-authors from NYU Grossman School of Medicine include Ariadne Rivera-Aguirre and Amanda M. Bunting, PhD. Additional co-authors are David Kline, PhD, Wake Forest University School of Medicine; Brandon D.L. Marshall, PhD, Brown University School of Public Health; Silvia S. Martins, MD, PhD, and Pia M. Mauro, PhD, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University.

Funding for the study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the NYU Center for Epidemiology and Policy.